Camilla Eriksson

Camilla Eriksson

I paint because some feelings just have to be shared.Strong ones, may they

be good or difficult. My paintings tell me their own stories. About me. About things I’ve felt and

experienced. Blue periods? More a need to dive into blue, red, orange, blue or any other colour for a

while. While painting I take time to observe. And feel. And get obsessed. It’s

all strict, wonderful and crazy self-indulgence. My surroundings know there are feelings I need to

express.

Painting is an amazing journey. People share their thoughts, emotions and inner

life with me throughout the process. And it’s a buzz to see perfect strangers fall in

love with my work, seeing a filthy factory window, the wilderness of Greenland,

figures that may be penguins, cranes or Masai tribes – or something completely

different, and make sure the painting finds its home.

It’s seriously moving, and I love all the interpretations. After all, it’s in the eye of

the beholder.

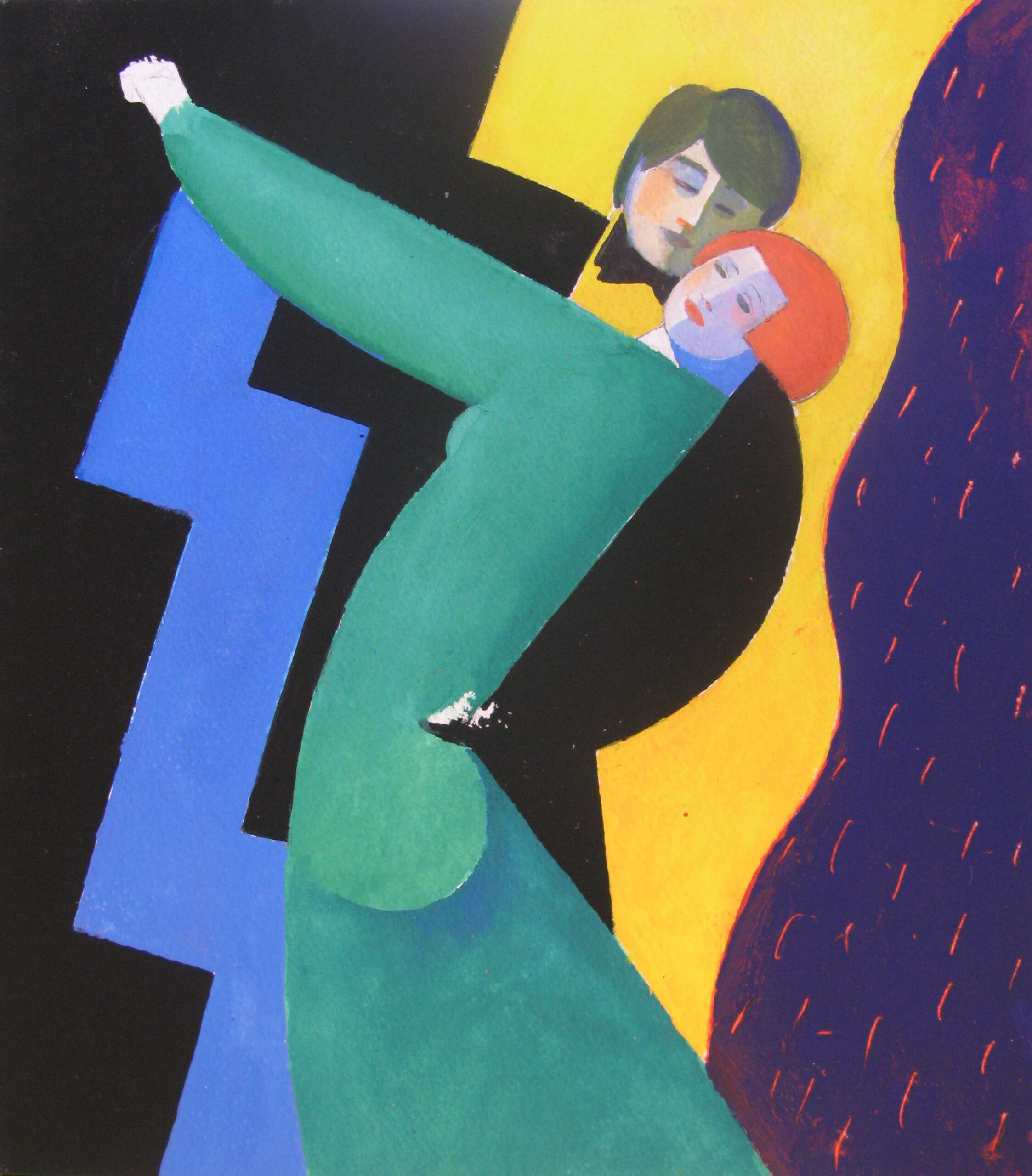

Björn Almviken

BJÖRN ALMVIKEN

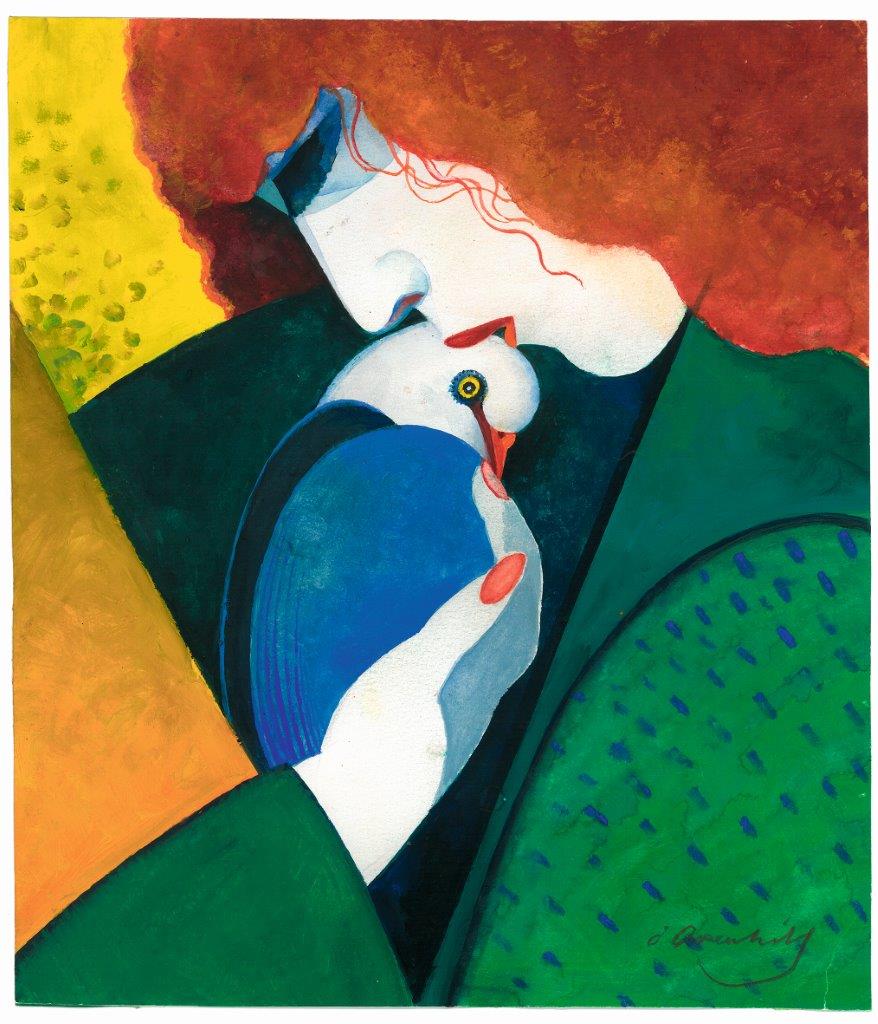

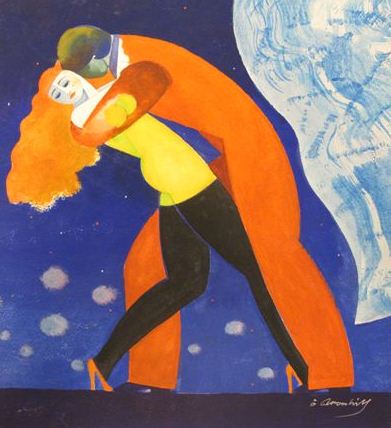

Åke Arenhill

Åke Arenhill

Anna Clarén

28 January – 26 February 2017

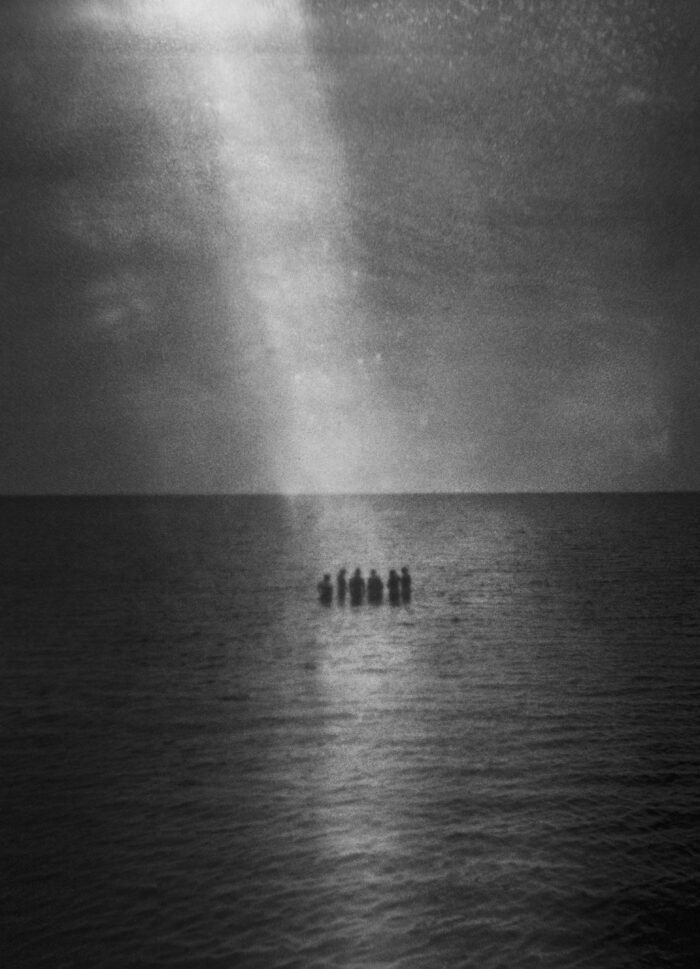

ANNA CLARÉN – UNDER

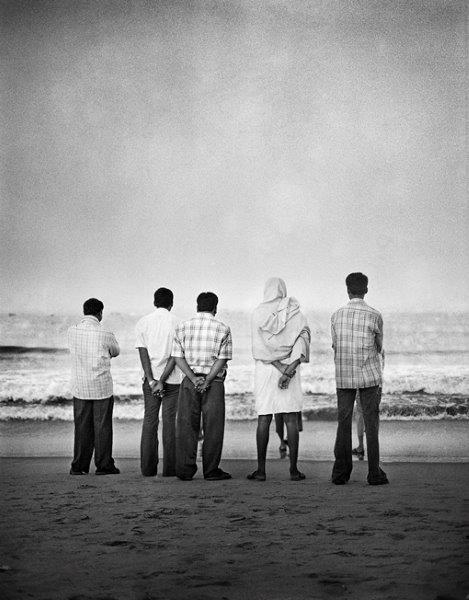

Anna Clarén’s photo art is highly autobiographical. After having seen her latest works I’m tempted to say skinless. Given the title Under, they differ from everything she has built so far on her career. Under might refer to under the surface but could also – in Swedish – be understood as a haul between then and now. Butterflies are responsible for the transport. Nameless butterflies who flutter in the tepid air in Fjärilshuset (The Butterfly House) at Haga. The butterflies bring her back to square one. It was with the butterflies she almost unconsciously entered her photographic path, a couple of decades ago. Then life and success interfered and the butterflies disappeared, maybe because she never was very interested in them to begin with. However, when life demanded a restart they returned. In Under – to borrow from her own words – she merely uses them as symbols of resurrection. I myself even understand them as the artist’s alter ego, the final stage of turning yet in a fixed manner. This time it doesn’t begin with a young girl’s dream of a fulfilling career as a photographer but instead at a turbulent life crisis that leads to something new and unexplored.

My first encounter of Anna Claréns photographic art took place at Fotografiska in Stockholm during the spring of 2013. The museum showed Close to Home, an exhibition which has since then reached far and wide and generated a photo book with the same name. It made an immense impression. The motifs were trivial and self-biographical, collected from her closest environments: her kids and husband, her parents and their parents, nature sceneries from Biskops-Arnö, Stockholm or Skåne, places where she had lived during longer or shorter periods. Clean pictures, minimalism stripped off everything but the most essential. Exquisite. What had them differed from all I had seen so far was however, the light and the shimmer of fragile happiness that radiated from it. But it was also alarming. Almost every photo was so filled with light that it seemed to be overexposed. Just a bit more light and the motif would fade and fly away as the morning mists in early summer, as the memories of the past.

The stillness and silence in Close to Home is total and leads thoughts towards artists such as Jan Vermeer van Delft and Wilhelm Hammershøi, both known for creating big and unforgettable art out of trivial acts and empty rooms. But there ends all similarities. Both Wermeer and Hammershøi are quite neutral when they approach their motifs; Anna Clarén loads her poetical and beautiful photos with a minor sued sadness emanating from the understanding of the fragility in life and the moment. It is an understanding that gradually has matured after her award winning debut book Holding, a sort of photographic diary starting from the summer of 2006. The book awoke the curiosity of the journalist Christoffer Barnekow. He wanted to learn more about her life and the art and met her for an interview in 2009. It was published in Konstkatalogen No 1 the same year. Talking about how her photos had become more and more pale and almost ethereal she answered: “I fear the catastrophe. I’m afraid it will come before I even know it is a catastrophe. I see an accident in slow motion. It will blow, but I don’t know where. Maybe it is this pale. Soon it’s over. Soon it’s gone”.

In 2009 Anna Clarén also started the project Close to Home – all in all about 60 pictures. As an epilog she writes: “Most pictures are taken during 2009 to 2012, during a period when an immense lot of beautiful things were given to me. I have had three children and a husband. We are living in a house in the middle of the beautiful Swedish nature”. And the photos are shimmering of light. And sadness.

In Under the tone is quite different. The tender sadness is transformed into a deeper minor and the color scale is much darker than in Close to Home. The evil forebodings seem to have come true. The family is no longer the focus, nor is the home. In some short lines Anna Clarén writes those grave disappointments a couple of years ago which made her life turn, made her disappear under the surface, blindly swimming. More concrete: She fled to Fjärilshuset på Haga where she more or less lived for six long months, delegating her emotions to her camera and filling thousands of photos with a new poetry. Touching, beautiful. Also this form of poetry is fragile but also darker, more troubled and evidently hunting a resurrection and a new life, a new light. And it is coming. In most of the photos there is, far away, a hint of light to be seen. A dawn. A new day and a new freedom wait outside the secured glass walls.

Britte Montigny

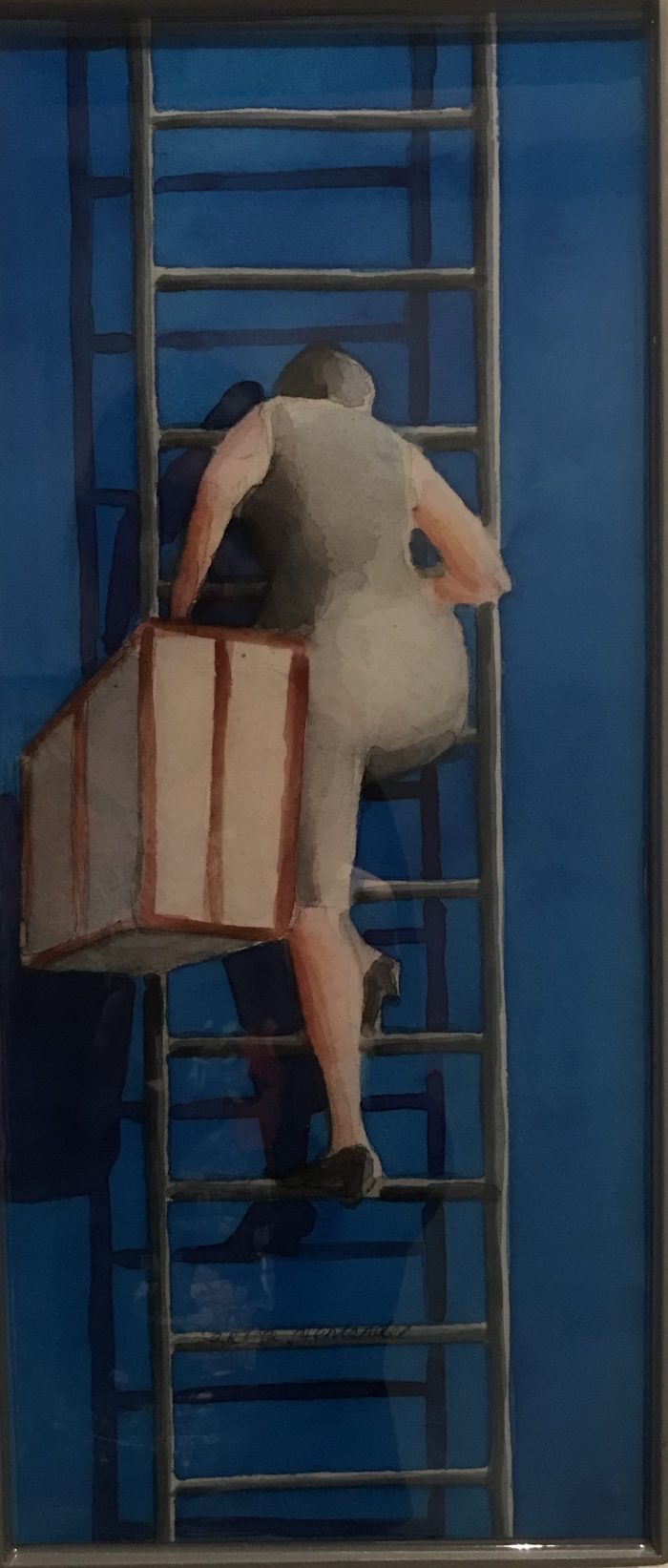

I’m not very interested in butterflies. I do not know the latin names of the different species, how long they live or what they eat. I am after the feeling of being in a state of transition. Of being in-between the old, the ingrained and the safe life behind you and the new, without knowing what the new will be like. Some might call it a crisis. I think most of us have been there. Maybe in having to go through a divorce or having to say good-bye. In moving away or in changing jobs. This gap in-between can be scary and lonely place.

In the winter of 2015 life took me back to that gap. A series of disappointments forced me to change path, to give up much of what had been my identity. Nothing was the same. In search of something familiar or in search of comfort I went to Fjärilshuset in Haga in Stockholm. During 6 difficult months I took pictures almost every day. One hundred rolls of film were exposed in my camera.

Often I had the feeling of swimming under water. I held my breath and focused on swimming. I told myself –almost there, just a little more, you can do it. Maybe you have to sink, to touch bottom before life can turn into something else? I want to tell a story about rebirth. A larva that becomes a chrysalis and finally a butterfly.

Anna Clarén

2017-01-12, Biskops-Arnö

Anna Clarén was born in Valje and grew up in Lund in Skåne in the south of Sweden. Her breakthrough as an artist came with the series “Holding”. Her book with the same name was awarded “Photo-book of the year” by the Swedish Photographers Association in 2006. She has also produced the series “Puppy Love” and “Close to Home”. The latter project was exhibited in 2014 in Malmö Museum. Anna Clarén also formed a part of the exhibition “A way of life” on the Moderna Museet (Museum of modern art) in Malmö and Stockholm the same year.

Her latest photo-series “Under” is now exhibited in its entirety for the first time.

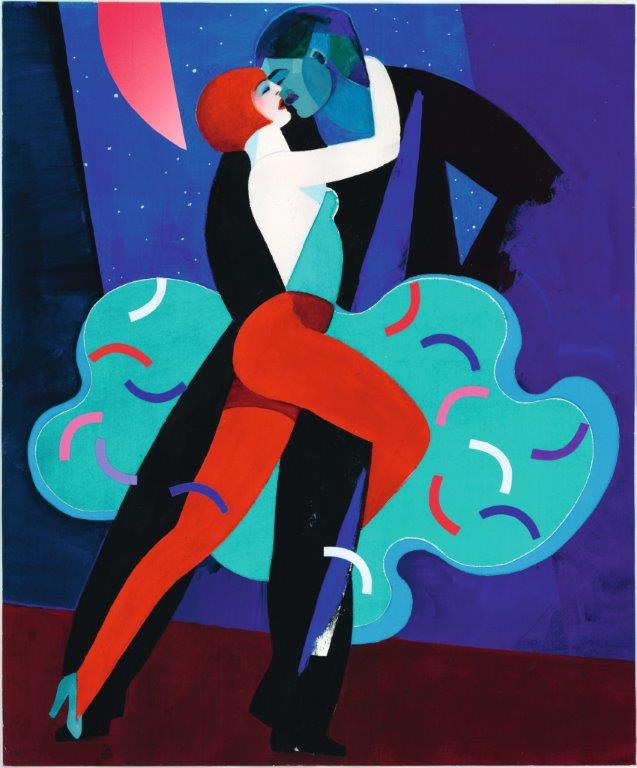

Johan Petterson

JOHAN PETTERSON

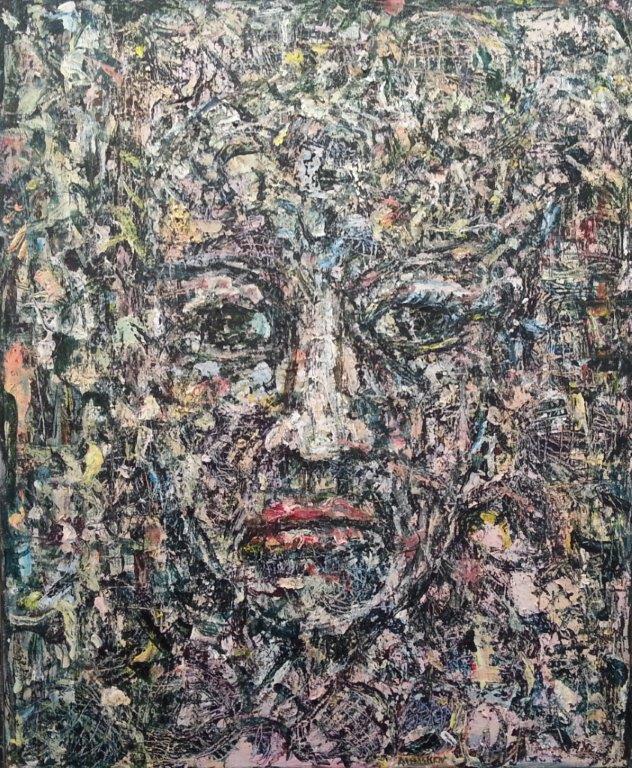

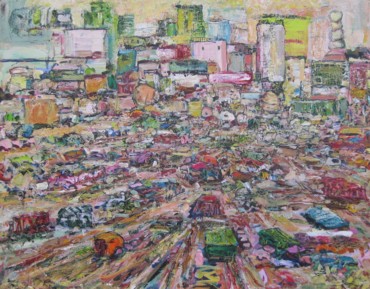

After five years, Johan Petterson is now back at Galleri Final with a series of New Paintings. On the one hand, they focus on flowers, and on the other, they focus on birds and frogs. This is a new and different world in Johan Petterson’s universe, where human beings, who are often part of his artistic properties, are not welcome. The flowers greet us in their still life composition of artistically moulded garden urns, filled with airy bouquets. At times they conjure up images of flaming roses, but most often they seem to be gathered from an imaginary flora. Linnaeus would have been amazed, but on the other hand – and as Johan Petterson has also asked himself – what do flowers care about their names in Latin? In floral bouquets, everything is a dance between colors and forms (underlined by the balanced encounters between acrylic and oil) as well as variations in textures and shades where names and even species are indifferent.

In these paintings, created as variations on the Flora theme, the brush strokes are rapid, the shapes are implied rather than clearly stated and the colors are carried out by a luminous intensity when they stand out against the backdrops, neutrally maintained in black or gray. In the larger flower paintings, little birds can be found, most often tree sparrows, making their way into the picture, creating a link to the exhibitions’ other dominant motifs: birds from the Nordic fauna. As seen in the Flora paintings, Johan Petterson quite deliberately builds a bridge to 16th century Netherlands, the classical period of big floral compositions. To connect tradition to his art is a typical way for Johan Petterson to work. Not because he believes that “it was better before”, but because tradition is highly useful in looking forward to the future. In true post-modernism spirit, he does not attempt to build walls between “now” and “then”. On the contrary, he wants to preserve, renew and create ways into the future. And that does not only concern his updated floral still lifes, where he seems to capture the fleeting moment in flight. This applies equally to both the landscape and animal paintings, as well as those genres that stem from 16th century Dutch art.

But in Johan Petterson’s studio in Stockholm, landscapes as well as groves of trees and shrubberies sometimes transform into ornamental “no-mans lands” where magpies rest and blackbirds sing on silent summer nights and where small birds play hide-and-seek among the twigs and the majestic necks of white swans materialize out of the black water of a forest lake. When drawn out of their natural environments, we are forced to look at them with new eyes, to experience them as guests in a world that is becoming more and more urban. An owl, who could have been taken from a work of Hieronymus Bosch, sits on a closed gate, a border between two worlds that Johan Petterson leaves to us to define. And the owl, in turn, looks at us with eyes that no longer can be surprised or amazed. In Johan Petterson’s art, the owl acts as a messenger between different realities. A surrealistic trace that is even more accentuated in the painting entitled Mitt i Malmö (In the Middle of Malmö). A title that confuses since there is no connection to Malmö in the painting at all. It depicts a frog – a Scania tree frog, but it can also be a bewitched prince or a princess awaiting that liberating kiss. In Mitt i Malmö , the frog sits on an opalescent circular disk, an oversized dewdrop in the ornamental no-mans land – or is it on a full moon in a distant galaxy? Like the owl, the frog raises many questions, but once again Johan Petterson leaves it to us to find the answers.

Britte Montigny

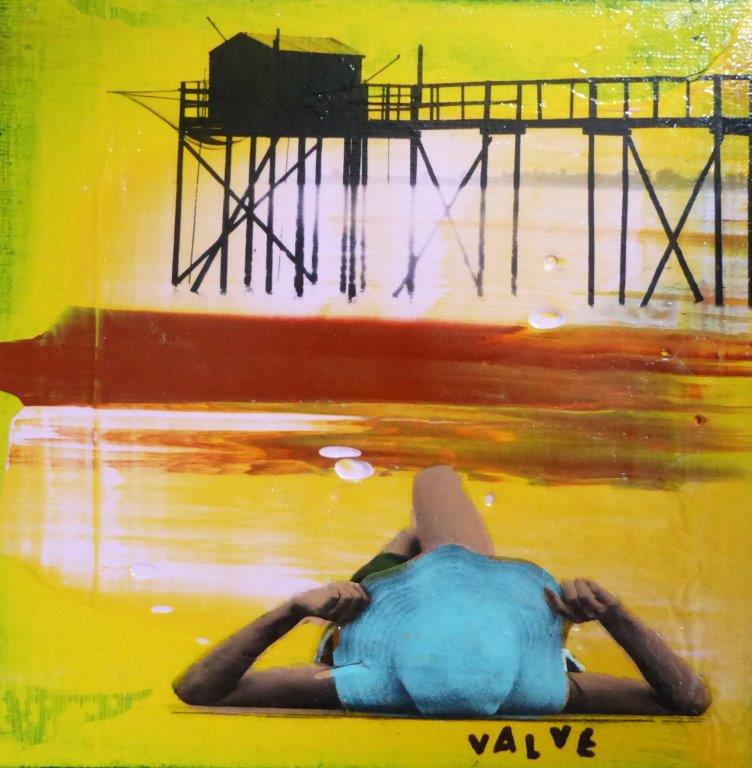

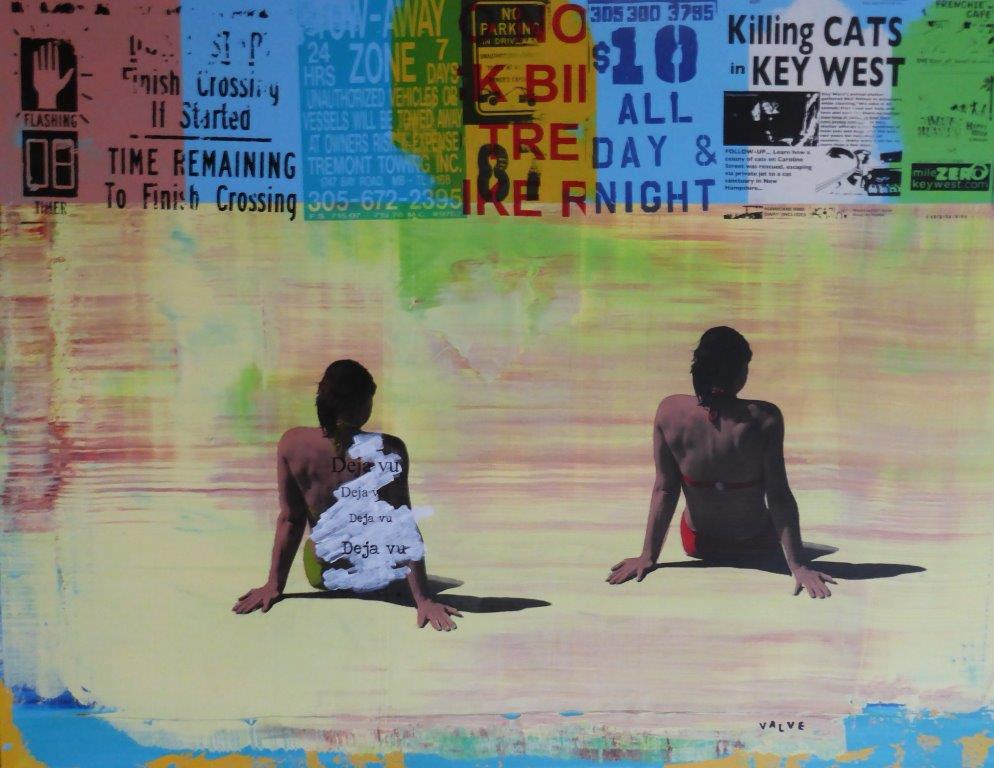

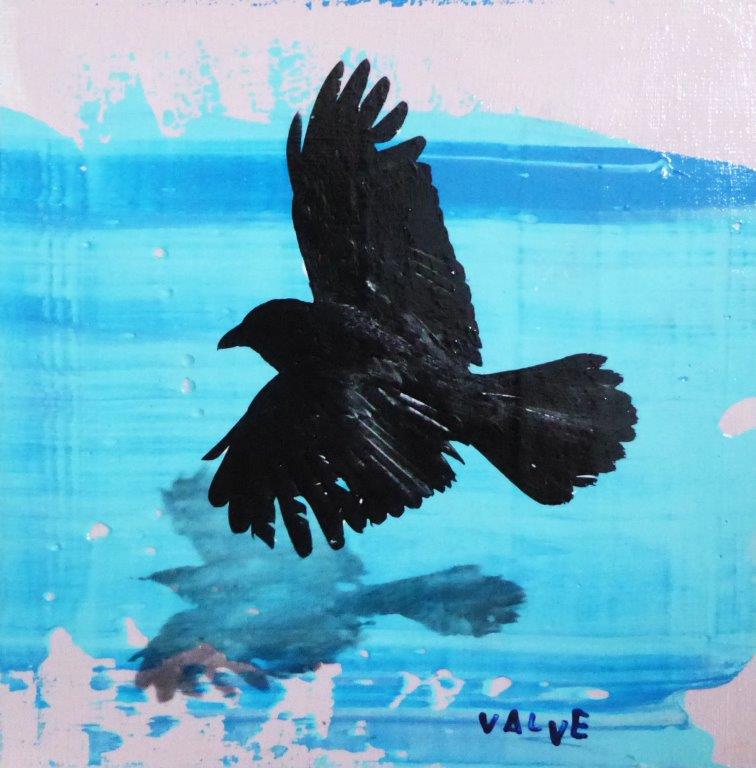

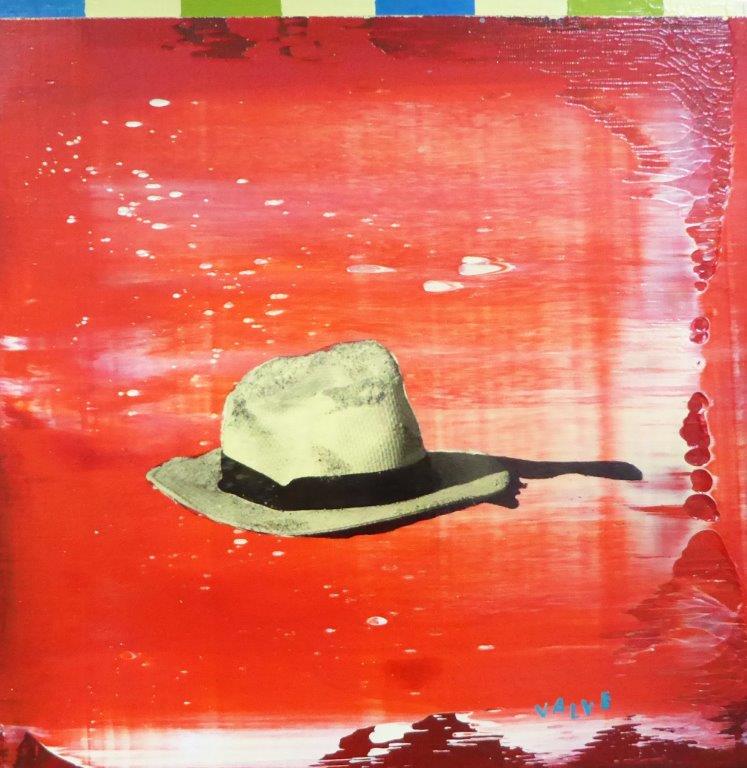

Karl Valve

KARL VALVE

Karl Valve spent his early years in Tullinge just south of Stockholm where he grew up at the same time as graffiti culture was starting to emerge and develop. Without being a graffiti artist himself, he nevertheless filled his notepads – ‘black books’ – with drafts of bold letter combinations, sometimes spiced up with figurative elements. The turning point came when he moved to Malmö and discovered P-huset Anna, a multi-storey car park with so-called ‘legal walls’. This was a favourite haunt of young graffiti artists, since it gave them the chance to paint and develop their creativity without the risk of being nabbed by the police. Their spray cans were bought in Copenhagen, which also had a broad selection of graffiti magazines.

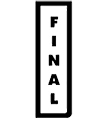

These early experiments with graffiti were the precursor to Valve developing a deeper interest in art and especially in its technicians, since for him it wasn’t just about applying paint to a canvas (or other medium) in a figurative or non-figurative manner. In replacing spray cans with putty knives and adding layer upon layer of paint – nowadays up to ten of them – he gave his surfaces a poetic depth which invited interpretation and clarification. Important sources of inspiration for the development of his work with putty knives were such artists as Gerhard Richter (Bach Suite, 1992) and Ola Billgren, who in the same decade created his gleaming red “echoes of Pompeii”. The artist who was to have the greatest effect upon him, however, was the American Robert Rauschenberg. In the 1950s, as part of his development of late 1910s Dadaism, he introduced combines and assemblages as artistic media. The most famous example of the latter is undoubtedly his Monogram of 1959, a goat with a car tyre around its belly, but it was primarily Rauschenberg’s combines which from an early stage came to fascinate Valve. For Rauschenberg, these often work in the same way as contemporary documents or diary entries. Photographs, newspaper clippings, letters of the alphabet, and streaks of colour are combined into collages rich with association. In Valve’s current exhibition which he, with a dash of nostalgia, calls Life on the Seashore, this relationship with Rauschenberg is as evident as the differences are striking. Valve too works with combinations of colour, photographs, figurative painting and letters, but whereas Rauschenberg is extrovert in his work, Valve is introspective, otherworldly and lyrical. A streak of contemplative poetry runs through the current exhibition, not least in its bird motifs.

Without having any real idea of how the finished work will look, Valve begins by applying layer upon layer of acrylic paint to the canvas. Shifts between thin glaze and more impasto textures create a relief-like effect in the paint, the nuances of which determine the content of the rest of the painting. In Fågelmålningarna (the Bird Paintings), Valve’s palette seems to have carried his thoughts to the beach where the sea ebbs away, where the shifting light of the heavens is reflected from dawn to dusk in sand that remains ever moist and where the sun appears as a shining globe. His paintings are thus transformed from abstract lyricism into summer beaches, into a setting for birdlife but also for bathing, boats and beach cabins: a setting with horizons both deep and implicit.

The whole exhibition is characterised by a quiet beauty closely allied to nature. Should we then refer to Valve as a nature poet? ‘No,’ he says, he is a child of the city, while acknowledging a strong attraction to Taoism, the Chinese philosophy which in nature and through inward contemplation and meditation seeks to find ‘the Way’ to inner harmony and an understanding of life. One of Valve’s favourite books is Benjamin Hoff’s Tao of Pooh, an unsurpassed source of wisdom in which Valve finds a soulmate in the form of Pooh Bear’s friend Piglet. Taking Piglet by the hand is in fact an excellent way to find the right path into Karl Valve’s multi-layered and deeply poetic world.

Britte Montigny