25 November – 22 December

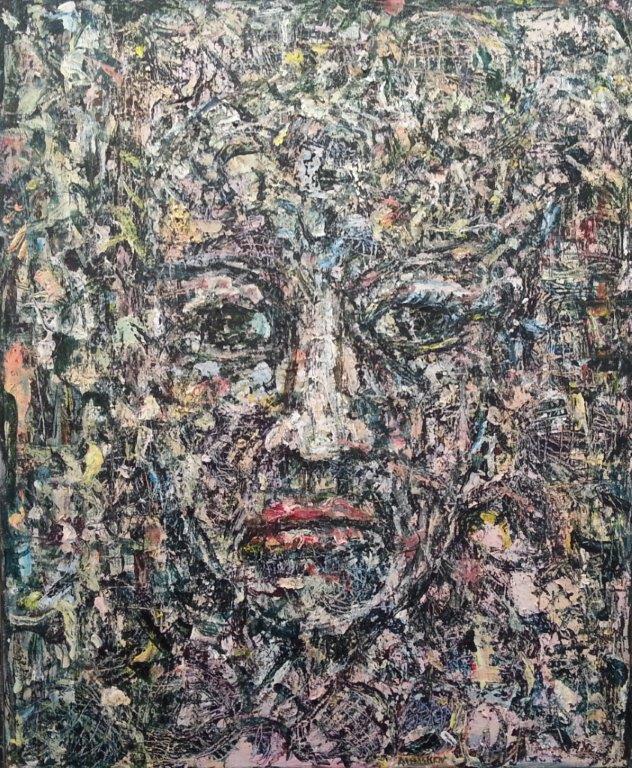

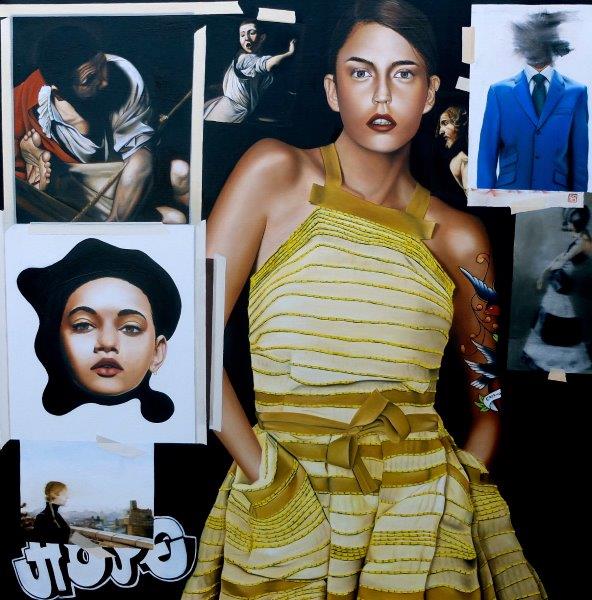

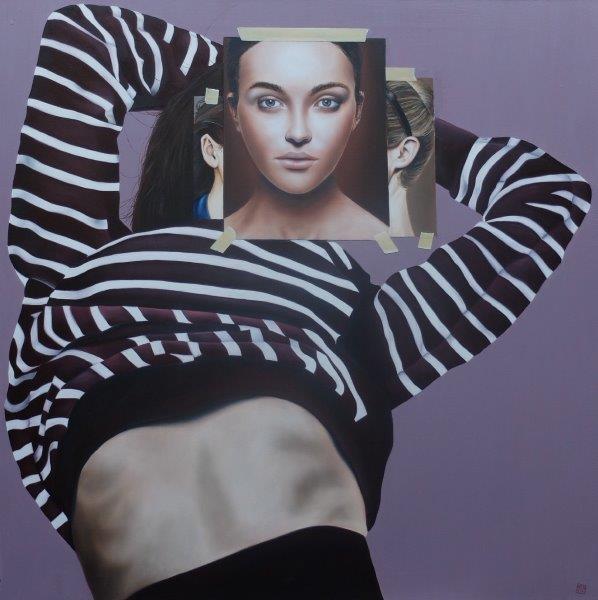

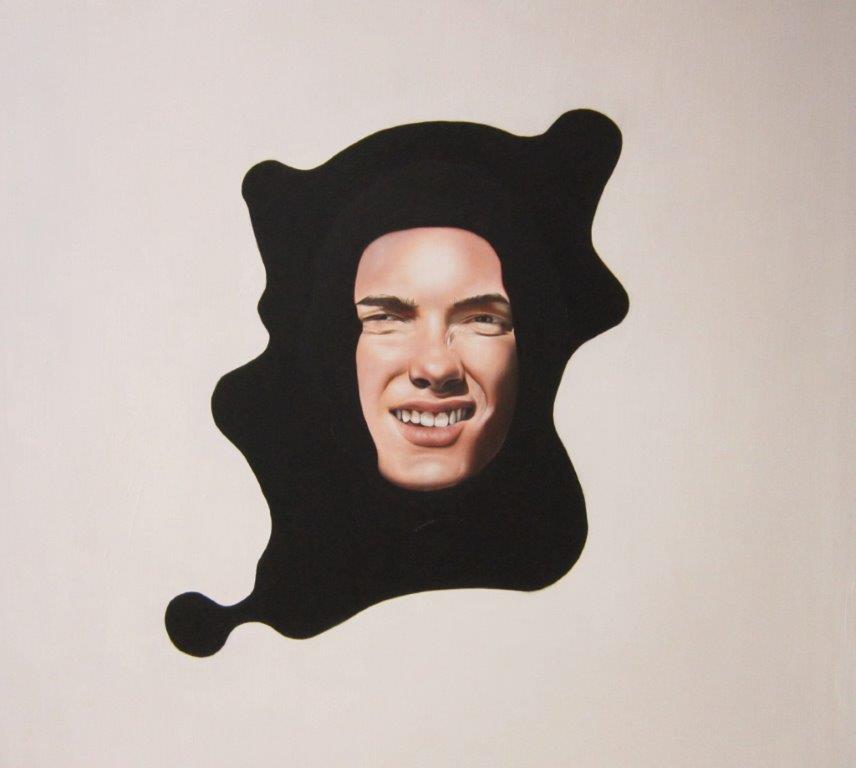

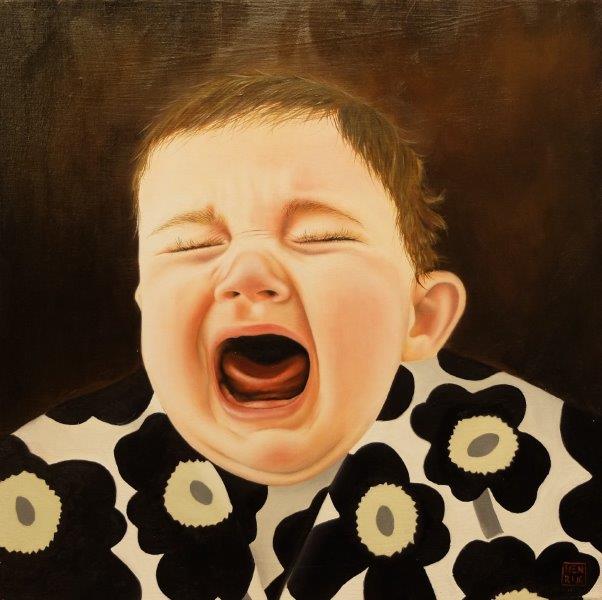

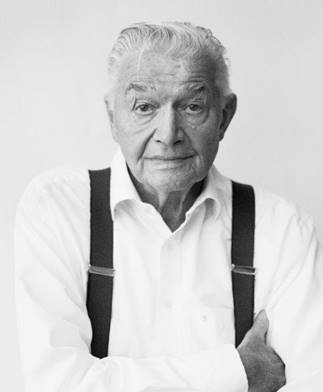

Johan Thunell

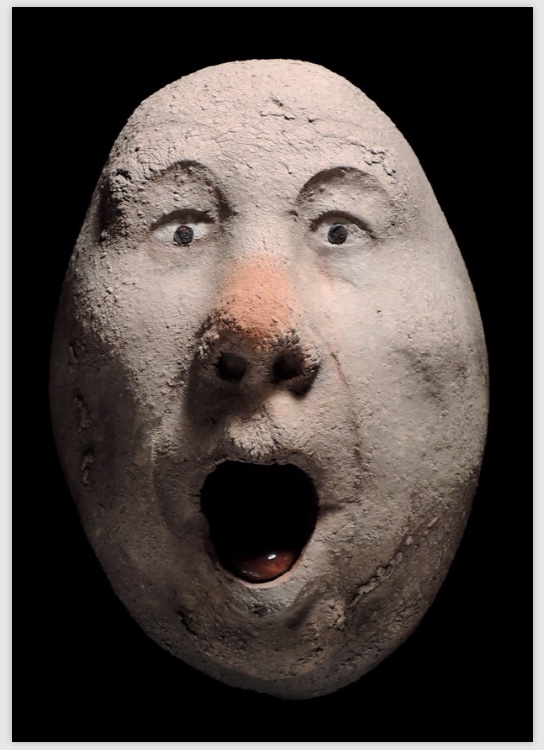

“New faces”

I established my studio in the early seventies after my training at the Croydon College of Art,

London. In the early days, inspired of what I saw of work from Japan and England. I mainly made domestic ware in stoneware and porcelain. In later years the emphasis has shifted towards sculptural work; renderings of beast and man in stoneware and raku. Quite recently my interest has come to focus on human physiognomy. Johan Thunell starts his work with sketching charismatic faces from human being while he is waiting for a bus, train, airplane or any other suitable occasion. Using the sketch as a model he starts to wheel thrown the clay and create fascinating human faces. He has exhibited at museums and galleries all over the world. He is also an frequent exhibitor at international artfairs In Europe, the US and Asia.

Born 1946. Lives and work in south of Sweden.